The basic ideas for Aphrodesia came slowly over many years. My first story notes date from 2007, but I first became interested in perfumes more than a decade earlier.

The basic ideas for Aphrodesia came slowly over many years. My first story notes date from 2007, but I first became interested in perfumes more than a decade earlier.

In the mid-80s, I was working in London, in an office behind Selfridges, and I often spent part of a lunch hour in that store. Like most big department stores, the first thing you saw upon entering the main doors was an array of perfume stalls. The variety pricked my interest, and I began talking with the stall attendants and collecting samples. At the same time, it so happened there was a bookstore across the street from my office that specialized in literature on perfumes. I bought a four-volume boxed set of reference books by H&R (Harmann and Reimer, an international perfume company). The classification systems in these volumes made good sense to my scientific mind, and the ideas about what kinds of fragrances appealed to what sorts of people were intriguing. For instance, it turns out my wife and I both prefer Oriental Notes (which possibly has contributed to our lifelong compatibility).

Over the next ten years or so, I read other books, collected articles, and more-or-less casually accumulated information for the possibility that I might eventually write a story centered on perfumes.

Flash forward to 2007. My wife is working several weeks a year at a museum in Paris, and for part of the time, I tag along. On this occasion, I notice there’s a Fragonard perfume museum near the Opera. I’m chatting with one of the employees, and she tells me about ISIPCA and the Osmothèque. ISIPCA is the world’s top perfume school, and the Osmothèque is billed as the “living museum of perfumes.” They’re located on the same premises in Versailles. Next day, I hop on a train and go out there.

Long story short, I lucked into to spending a whole afternoon with Jean Kerléo, founder and president of the Osmothèque, and a young Italian man, Marcello Aspria, who has an excellent website on perfumes. At one point, I asked Kerléo if creation of an aphrodisiac was still a goal of perfumers, and he said, “Yes.”

That was my inspiration. I started writing and soon accumulated a lot of questions to which I couldn’t find answers. So next year, ahead of my wife’s annual Paris sojourn, I requested another interview with Kerléo, which he graciously granted. Not only did he answer my questions, but he also treated me to one of the rare tours he gives into the basement vault where the Osmothèque stores its unique collection of fragrances.

Twice educated by Monsieur Kerléo (who spent thirty years as the Master Perfumer for Jean Patou), I scrapped some of my earlier ideas and dived into writing a story that would both honor his profession and provide a wild ride for anyone interested in aphrodisiacs.

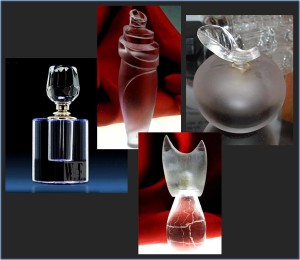

The photos below are by John Oehler and are licensed through Creative Commons.